“We can use it to print sensors on 3D surfaces,” explains James Yang, an engineer at GE Global Research, who is leading the project. “One day they could be anywhere.”

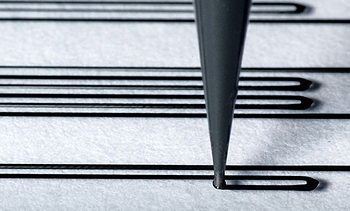

Yang and his team are using a computer-controlled syringe filled with special inks to print the sensors. The “automated pen” deposits material onto a surface to build up a part. One type of ink uses a conductive mix of fine silver, copper, platinum and other metal particles. Another one uses metal oxides instead of pure metals to introduce resistance.

Direct Write is ideal for producing small-scale structures with fine features, such as sensors and antennae.

The technology dates back to the 1990s when Darpa, the US Defense Department’s research agency, was looking for a way to print electrical circuits on flexible surfaces. The technique is now used by the electronics industry to produce mobile phone antennae.

GE"s Direct Write technology allows intricate sensor structures to be created inside machines

Yang and his team are using Direct Write to print 3D sensors that can withstand temperatures of 2,000°F (1,093°C) and can handle high mechanical forces. These sensors could help engineers to understand better what happens inside machines. Users could collect data they could not access previously, optimise machine performance and spot problems before they get out of hand.

According to Yang, the technology fits in with GE’s vision for creating more intelligent machines linked to the emerging Industrial Internet. “Using Direct Write, you can embed more intelligence within a structure, so that the structure can sense and respond to its environment,” he says.

“For example, one application GE is developing is to build small devices such as sensors on parts to measure things like temperature or strain,” Yang continues. “Temperature and strain are two key features to track in the kind of products we make like jet engines that function in hot, harsh environments. Using Direct Write, we can print sensors onto parts and get them into places we couldn’t put them before. This, in turn, will enhance the real-time data analytics and condition monitoring that can be performed on our products.”

Another attraction of the technology is that it can be integrated with automated manufacturing processes for higher throughputs.